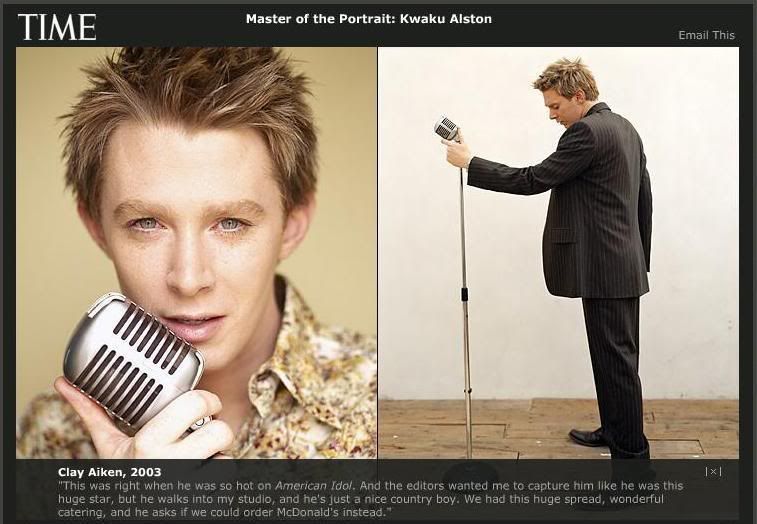

A multi-page feature in Time Magazine…….that is a pretty amazing feat for any person, but especially for a young person who was thrust into the limelight only months before. And the rumor running around the internet was that Clay Aiken almost made the cover of the magazine.

A multi-page feature in Time Magazine…….that is a pretty amazing feat for any person, but especially for a young person who was thrust into the limelight only months before. And the rumor running around the internet was that Clay Aiken almost made the cover of the magazine.

The Clay Aiken feature in Time Magazine ran in the October 5, 2003 issue and caused much talk and discussion with not only Clay’s fans, but also the music world. It said a lot, not only about Clay Aiken, but about the music business in general.

While reading the article again, after a few years, a few things stood out to me.

- The author assumes the superiority of music industry tastes to those of the music-buying public.

- Clive Davis of RCA concedes that music labels pander to radio and MTV.

- Artists that market themselves as sex objects are not better musicians.

- It was a mistake for the record company to characterize Clay’s fans as ones that demand “blandness.”

- Music industry executives are out of touch with what interests the public.

Of course, when you read this article over again, you will probably see other things that catch your eye. If so, please let us know through your comments. I bet we could have a great discussion about this article.

Josh Tyrangiel was the editor who wrote this article about Clay Aiken. The following information on Josh was found on the website, Digital Hollywood.

Josh Tyrangiel, Managing Editor, TIME.com: As managing editor of TIME.com, Josh Tyrangiel oversees TIME’s daily news site, which draws more than 5 million unique visitors a month and in February 2007 was named “Website of the Year” by the Magazine Publishers of America. Tyrangiel joined TIME in 1999 as a staff writer and music critic, and was named managing editor of TIME.com and assistant managing editor of TIME in September 2006. He continues to write about the music industry. Tyrangiel has written cover stories on Bono, Kanye West, the Dixie Chicks and Bruce Springsteen, as well as articles about politics, international relations, food, academia and sports. He has interviewed and profiled former Democratic presidential candidate John Kerry, former Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert, Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer, Houston Rockets center Yao Ming, and Oscar winners Sean Penn, Nicole Kidman and George Clooney. Tyrangiel has also twice served on the panel of judges for the influential Shortlist Music Prize. Prior to his arrival at TIME, Tyrangiel was a producer at MTV News. He also wrote for Rolling Stone and Vibe. Tyrangiel received his B.A. from the University of Pennsylvania and his M.A. in American Studies at Yale.

I hope you enjoy reading the article.

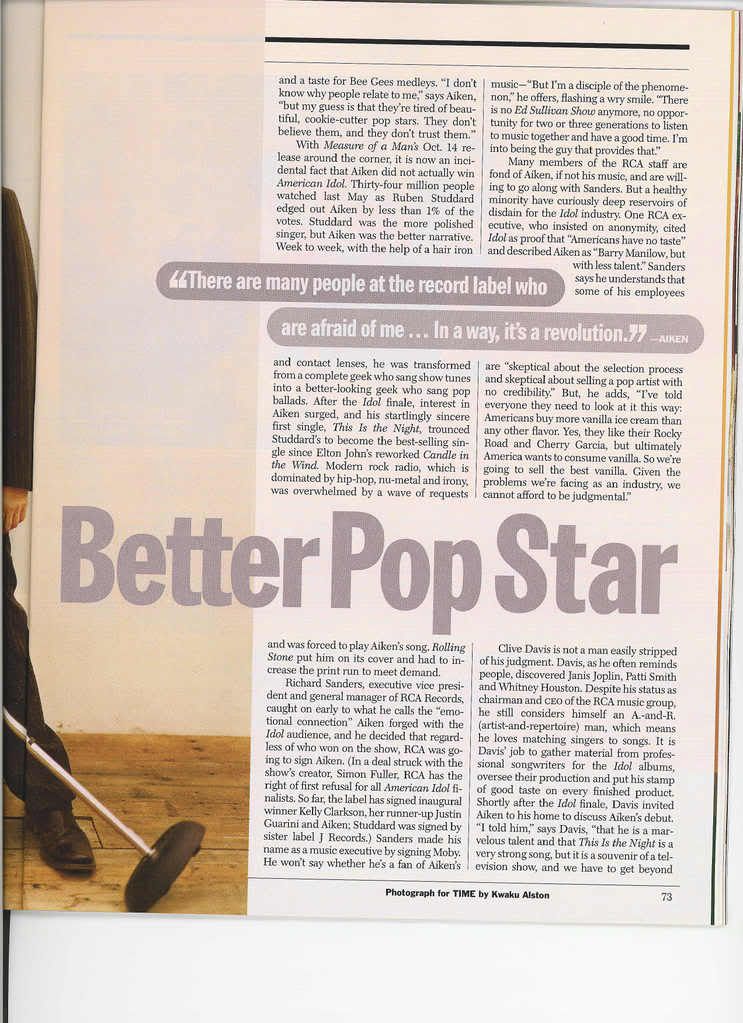

Building a Better Pop Star

10/05/2003

The record industry needs a savior. American Idol runner-up Clay Aiken could be it. Now will he play along, or is his style too far off-key?

Ask the employees at Clay Aiken’s record label, RCA, if they would listen to Aiken’s debut album, Measure of a Man, by choice, and the response is almost uniform: a lengthy pause followed by laughter. RCA was the home of Elvis Presley, and its current roster includes critical favorites like the Strokes and the Foo Fighters. It’s a rock label. Aiken, who came in second on the most recent installment of American Idol, is not only not a rocker, but, as he says in his aggressively self-deprecating way, “I’m not an artist. I’m just a guy who was on a reality show—and I didn’t even win!” Humility aside, Aiken, 24, doesn’t mind being doubted because he believes in his bones that his detractors are wrong. “There are many people at the record label who are afraid of me,” he says. “They don’t understand the reasons that someone as uncool as me is here. In a way—and this is a horrible word to say, and once I say it you’re going to print it—it’s a revolution.”

The revolution of which Aiken speaks is a TV show. In two seasons on the air, American Idol has snatched the notoriously vague process of selecting musical talent away from music executives and put it in the hands of ordinary Americans. In a convenient syllogism, Aiken believes that since everyday people chose him as their hero, those at RCA who don’t like him or his music are biased against everyday people. He may be right. It’s also possible that his denigrators love music—and the process of making music—far more than Aiken can imagine and that they resent having their passion marginalized by anyone with a telephone and a taste for Bee Gees medleys. “I don’t know why people relate to me,” says Aiken, “but my guess is that they’re tired of beautiful, cookie-cutter pop stars. They don’t believe them, and they don’t trust them.”

With Measure of a Man’s Oct. 14 release around the corner, it is now an incidental fact that Aiken did not actually win American Idol. Thirty-four million people watched last May as Ruben Studdard edged out Aiken by less than 1% of the votes. Studdard was the more polished singer, but Aiken was the better narrative. Week to week, with the help of a hair iron and contact lenses, he was transformed from a complete geek who sang show tunes into a better-looking geek who sang pop ballads. After the Idol finale, interest in Aiken surged, and his startlingly sincere first single, This Is the Night, trounced Studdard’s to become the best-selling single since Elton John’s reworked Candle in the Wind. Modern rock radio, which is dominated by hip-hop, nu-metal and irony, was overwhelmed by a wave of requests and was forced to play Aiken’s song. Rolling Stone put him on its cover and had to increase the print run to meet demand. Richard Sanders, executive vice president and general manager of RCA Records, caught on early to what he calls the “emotional connection” Aiken forged with the Idol audience, and he decided that regardless of who won on the show, RCA was going to sign Aiken. (In a deal struck with the show’s creator, Simon Fuller, RCA has the right of first refusal for all American Idol finalists. So far, the label has signed inaugural winner Kelly Clarkson, her runner-up Justin Guarini and Aiken; Studdard was signed by sister label J Records.) Sanders made his name as a music executive by signing Moby. He won’t say whether he’s a fan of Aiken’s music—”But I’m a disciple of the phenomenon,” he offers, flashing a wry smile. “There is no Ed Sullivan Show anymore, no opportunity for two or three generations to listen to music together and have a good time. I’m into being the guy that provides that.”

Many members of the RCA staff are fond of Aiken, if not his music, and are willing to go along with Sanders. But a healthy minority have curiously deep reservoirs of disdain for the Idol industry. One RCA executive, who insisted on anonymity, cited Idol as proof that “Americans have no taste” and described Aiken as “Barry Manilow, but with less talent.” Sanders says he understands that some of his employees are “skeptical about the selection process and skeptical about selling a pop artist with no credibility.” But, he adds, “I’ve told everyone they need to look at it this way: Americans buy more vanilla ice cream than any other flavor. Yes, they like their Rocky Road and Cherry Garcia, but ultimately America wants to consume vanilla. So we’re going to sell the best vanilla. Given the problems we’re facing as an industry, we cannot afford to be judgmental.” Clive Davis is not a man easily stripped of his judgment. Davis, as he often reminds people, discovered Janis Joplin, Patti Smith and Whitney Houston. Despite his status as chairman and CEO of the RCA music group, he still considers himself an A.-and-R. (artist-and-repertoire) man, which means he loves matching singers to songs. It is Davis’ job to gather material from professional songwriters for the Idol albums, oversee their production and put his stamp of good taste on every finished product. Shortly after the Idol finale, Davis invited Aiken to his home to discuss Aiken’s debut. “I told him,” says Davis, “that he is a marvelous talent and that This Is the Night is a very strong song, but it is a souvenir of a television show, and we have to get beyond that. It is my feeling that when you get into being a career recording artist, the stakes are different. People want to see if you can stretch and evolve. They want to know if you have some edge.”

Before appearing on American Idol, Aiken was a special-education teacher in Raleigh, N.C. He is a devout Baptist who does not smoke or drink, though he claims to have a temper that emerges when he sees “people with disabilities treated like they’re 4 years old.” In his piety, Aiken can make Billy Graham seem like a rogue. He listened to Davis’ advice about edge and then respectfully asked that he not be required to sing any songs about sex. “Clive tried to tell me that saying certain words in a song—or as he says, ‘putting some balls into it’—isn’t bad, it’s just strong emotion,” says Aiken. “Well, there are certain words and emotions I don’t want kids hearing, and I’m not changing because they think it’s going to sell better. This is going to sound horrible, but I got 12 million votes doing what I did.”

Davis counters that Aiken is no longer selling to a TV audience. “You can’t worry about who bought the last single,” says Davis from his seat in an office studded with platinum-record plaques. “You can’t be paralyzed by what the public expects of you. We’re now competing against Justin and Christina and Avril and Pink, and if you allow the television audience to program your music, you will not be on radio and you won’t make MTV. And then where are you? We have to stay ahead of the curve.”

Aiken had been forewarned by Clarkson and Guarini that if he was happy with 50% of his completed album, he’d be “doing real good.” The problem, they told him, was that there were too many people wrestling for control of their music. “Simon Fuller did not create American Idol to be in the television business,” says Tom Ennis of Fuller’s production company, 19 Entertainment. “He created American Idol as a new way to find talent to manage and nurture.” 19 is the Idols’ official record label—RCA is the American distributor—and Fuller, who managed Annie Lennox before inventing the Spice Girls, is Davis’ contractual equal in choosing music for the Idol albums.

Here’s where the American Idol business gets dicey. Davis would like RCA to curate the careers of artists; Fuller wants his Idols to have long recording careers too, as long as they don’t forsake the Idol audience. (Fuller was incensed that Davis spent eight months refining Clarkson’s debut for radio rather than getting it to market as soon as possible.) “You have to serve many masters when you have that many people with a vested interest in you,” says Ennis. “You can’t skew yourself one way and not speak to the people who spent all that time watching you and voting for you.”

Ennis and 19 have market research on their side. As Davis suggests, avid music fans expect their stars to evolve. But the Idol audience, which has an unprecedented ownership stake in Aiken’s career, is not made up of avid music fans. A disproportionate number of copies of This Is the Night were sold at Wal-Mart and Target stores, and a large number of those discs were picked up in the check-out lane, where Sanders positioned Idol merchandise to catch the eye of people who wouldn’t think of stopping in the music section. “Our consumer is the middle 80% of the population,” says Gerry Lopez, president of Handleman Entertainment Resources, which stocks and manages music offerings at such stores as Wal-Mart. “These are moms and dads making $26,000 to $36,000 a year … We’re not catering to Napster or Kazaa folks, just people who like a nice song sung by a nice kid.” Because it pays the full retail price and doesn’t download music, the Idol audience is a record company’s dream; because it doesn’t have indulgent, wide-ranging tastes, it can be an artist’s nightmare. Studdard got so frustrated trying to tailor his upcoming album, Soulful, to the Idol audience that in early July he called his various managers and label representatives and, according to several sources, threatened to quit. “This is my car,” Studdard said, according to an executive who was on the call. “If you guys want to navigate, that’s great. If you guys want to drive, then you better get a new car.” Studdard is now working with Missy Elliott and R. Kelly on what an RCA executive termed “a credible, clean hip-hop album.”

If Studdard appears to be a Clive Davis kind of guy, then Aiken definitely sides with Fuller. “Simon Fuller is the one person I trust in all this,” says Aiken, and the proof is on Measure of a Man, which is the rare pop album completely free of innuendo, let alone sex. Instead of adding edge lyrically, Davis and another A.-and-R. executive, Steve Ferrera, were forced to play with Aiken’s sound, using crunchy power chords in place of benign synth pads and encouraging Aiken to put some power into his ballads. Says Aiken: “I’m very satisfied with my album. I grew as a singer, and Clive deserves a lot of the credit for that.”

Still, pop isn’t just music. It’s a package, and Aiken has had numerous frustrations with the way RCA has tried to tweak his image. Everyone—label, management and Aiken—was thrilled with Aiken’s Rolling Stone cover shoot, so photographer Matthew Rolston was hired to direct a video for This Is the Night. In it the story line was … Clay Aiken does a magazine photo shoot. “They had me in this tight little vintage T shirt and jeans and a leather jacket,” says Aiken. “And (Rolston) had me sing the song in one scene with this angst attitude—popping my neck and mean looks on my face … It’s trying to make me somebody I’m not. I’m not mean, and this is something the label just doesn’t get. ‘How the heck do we market this boy? We’re used to marketing Christina Aguilera and Dirrty. We can’t market clean!'”

Aiken laughs off most of RCA’s foibles—like the time he was forced to change his unstylish shoes before appearing at an industry convention, or the airbrushing of his eyes on the Measure of a Man album cover—because he believes that the label is clueless about how to market to an audience he knows instinctively. “I’m a battle picker,” he says. “I try not to get upset about all this marketing stuff because I’m saving it for the time that they tell me that I need to do a song about ‘Let’s hook up and have sex.’ But I’m like, ‘Do not—ugh!—don’t pretend that the public are a bunch of idiots! Don’t pretend that you know what they want and they don’t know what they want.’ That’s the stupidest thing I’ve ever heard in my life!” Of course, anticipating the tastes of the public—knowing that the world might be ready for a black woman to sing about respect, for example—is exactly what great creative executives do. They don’t make art, but they facilitate it, fight for it and nurture it, often in the face of public opposition or apathy. Record companies have always made plenty of music aimed at the heart of the market, but the frustration of the anti-Idol RCA executives—and many others throughout the industry—comes down to timing. At the exact moment that American Idol has created a surge of people who buy their music with their mints as an impulse item, file sharing has siphoned off nearly all the adventurous record buyers. That leaves a whole lot of people buying Sanders’ vanilla and very few interested in his Rocky Road.

It is telling that in just five months with RCA, Aiken has won most of his battles. The This Is the Night video was scrapped at considerable expense. His album is family-friendly pop. Aiken got to name his record Measure of a Man, even though Davis lobbied for any other title. The marketing department now says its strategy is to “let Clay be Clay.” “Revolution is a strong word,” says Aiken. “But RCA would not have picked me or Ruben. Simon Cowell would not have picked us. America has shown them that they don’t know what they’re talking about.”

Josh Tyrangiel, TIME Magazine