Do you remember the name, Allison Glock? If you have been a Clay Aiken fan since 2003, you probably remember that Allison was the writer that co-authored Learning To Sing: Hearing the Music in Your Life with Clay.

Today, Allison is a Senior staff writer at ESPN. She is also a contributing editor at Whole Living Magazine, a part of Martha Stewart Living and at Garden and Gun Magazine…yes, really!!

Allison is also a Whiting Writers’ Award-winner known for her soulful profile writing.

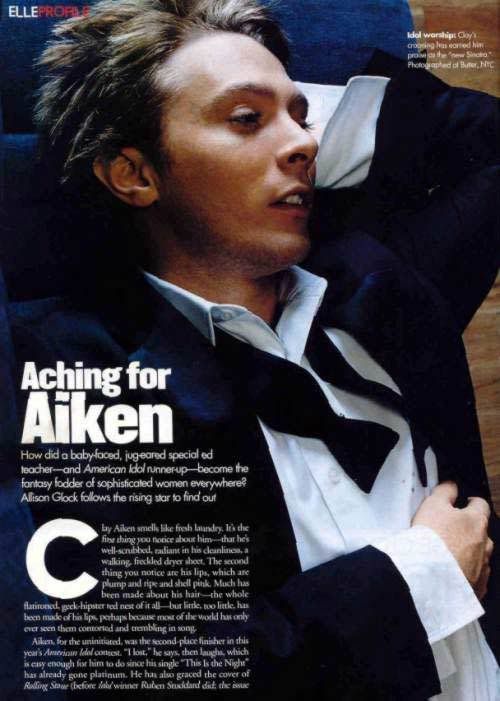

But to Clay Aiken fans, Allison became a name to remember when she worked at Elle Magazine. The September 6, 2003 Elle Magazine featured a three page article on Clay Aiken. Allison was the writer who gave the readers a look into the “rising star”, Clay Aiken.

Did you read the article when it first came out? Do you still have a copy of the magazine? I hope you enjoy reading the article again.

Aching For Aiken, by Alison Glock

How did a baby-faced, jug-eared special ed teacher—and American Idol runner-up—become the fantasy fodder of sophisticated women everywhere? Allison Glock follows the rising star to find out.

Clay Aiken smells like fresh laundry. It’s the first thing you notice about him—that he’s well-scrubbed, radiant in his cleanliness, a walking, freckled dryer sheet. The second thing you notice are his lips, which are plump and ripe and shell pink. Much has been made about his hair—the whole flatironed, geek-hipster red nest of it all—but little, too little, has been made of his lips, perhaps because most of the world has only ever seen them contorted and trembling in song.

Aiken, for the uninitiated, was the second-place finisher in this year’s American Idol contest. “I lost,” he says, then laughs, which is easy enough for him to do since his single “This Is the Night” has already gone platinum. He has also graced the cover of Rolling Stone (before Idol winner Ruben Studdard did; the issue allegedly sold more copies than any in the last two years, including the Justin Timberlake and Christina Aguilera, and Eminem covers, to name a few). His first album, Measure of a Man (RCA), out in mid-September, was ranked number three on Amazon.com back in July. His fans range from Diane Sawyer (who admitted to a serious Clay crush on Good Morning America ) to Neil Sedaka, who cried on camera when Aiken covered his hit “Solitaire.” “His voice is incredible–the pitch, the tone,” says Sedaka. “I think he’ll be the new Frank Sinatra.”

Aiken, for the uninitiated, was the second-place finisher in this year’s American Idol contest. “I lost,” he says, then laughs, which is easy enough for him to do since his single “This Is the Night” has already gone platinum. He has also graced the cover of Rolling Stone (before Idol winner Ruben Studdard did; the issue allegedly sold more copies than any in the last two years, including the Justin Timberlake and Christina Aguilera, and Eminem covers, to name a few). His first album, Measure of a Man (RCA), out in mid-September, was ranked number three on Amazon.com back in July. His fans range from Diane Sawyer (who admitted to a serious Clay crush on Good Morning America ) to Neil Sedaka, who cried on camera when Aiken covered his hit “Solitaire.” “His voice is incredible–the pitch, the tone,” says Sedaka. “I think he’ll be the new Frank Sinatra.”

“So much has happened in the past nine months that I haven’t had time to think,” admits the 24-year-old, from the back of the van that’s shuttling him from New York City to a concert appearance in Hartford, Connecticut. “Honestly, last night I was sitting in the hotel room crying for about an hour. I had to call someone back in Raleigh to wake them up because I needed to talk. Certain things have just hit me.”

Most recently, it was his inability to take a walk.

“I wanted to clear my head, and I realized that if I were to take a stroll in New York, I’d have to wake my bodyguard, Jerome, and then I’m not really alone, so what’s the point? I felt trapped and miserable. Sometimes I just want to go back to teaching.”

That’s unlikely, because while Aiken was, by all accounts, a gifted special ed teacher working mostly with grade-school children, he possesses a voice that’s impossible to ignore.

CALLING ALL CLAYMATES

“I was going to go to music school but decided against it,” Aiken says. “I didn’t see the point. Then I was running an after-school program at the YMCA, and I thought, Forget music, I love this. I want to work with kids with behavioral disabilities.”

“I was going to go to music school but decided against it,” Aiken says. “I didn’t see the point. Then I was running an after-school program at the YMCA, and I thought, Forget music, I love this. I want to work with kids with behavioral disabilities.”

But Aiken still sang at the Y, and when he sang, people noticed. Whenever he belted out a song—and he is a belter—the whole room quieted. Heads lifted. Eyes widened. Hearts swelled. When American Idol happened along, the mother of one of his students encouraged him to try out. Reluctantly, he did.

“I liked singing, but I never wanted to make a career out of it,” he says with a sigh. “When you work with kids who have autism, they don’t reciprocate any affection. You learn to find your self-worth within what you do, not what people tell you about yourself. Now with all of this, I really have flip-flopped. Also, I’m not much of a crowd person. It’s a lot to get used to.”

Unlike many of his fellow Idol finalists, Aiken didn’t grow up a fan: “I never idolized celebrities or musicians.” Even now, he can barely name one. “I liked that guy in The Pianist [Adrien Brody],” he offers lamely when asked which famous people he admires. As a boy growing up in a conservative family in Raleigh, North Carolina, Aiken enjoyed TV but was limited in his viewing options. Even The Golden Girls was considered too risqué. As a result, Aiken is the rare pop idol who knows next to nothing about pop culture.

“You know who I idolized? Mr. Rogers. Is there a market for the next Mr. Rogers? Because I’d love to do that. I’d much rather be quiet and important like him than live large and be some useless celebrity.”

Aiken’s ignorance of all things hot translates into a doofy authenticity and a captivating vulnerability. He’s so uncool, he’s cool. Dressed in loose khakis, a striped polo-style shirt, New Balance running shoes, and his ever-present WWJD bracelet, Aiken resembles a slimmed-down, Christian Charlie Brown. His hair is mussed but not in the artful, deliberate way it was on Idol. His teeth are white, square, and shiny. The only concession to his newfound stardom is a $15,000 diamond-studded Jacob & Co. watch that was a gift from the Idol producers but that he’s embarrassed to wear. “I was going to auction it off for charity, but it was a present, so I wear it. It’s really a woman’s watch. I liked it because it wasn’t as ostentatious. Ruben wears the men’s. He’ll probably show it to you.”

Aiken’s ignorance of all things hot translates into a doofy authenticity and a captivating vulnerability. He’s so uncool, he’s cool. Dressed in loose khakis, a striped polo-style shirt, New Balance running shoes, and his ever-present WWJD bracelet, Aiken resembles a slimmed-down, Christian Charlie Brown. His hair is mussed but not in the artful, deliberate way it was on Idol. His teeth are white, square, and shiny. The only concession to his newfound stardom is a $15,000 diamond-studded Jacob & Co. watch that was a gift from the Idol producers but that he’s embarrassed to wear. “I was going to auction it off for charity, but it was a present, so I wear it. It’s really a woman’s watch. I liked it because it wasn’t as ostentatious. Ruben wears the men’s. He’ll probably show it to you.”

Standing over 6′ tall but weighing only 145 pounds, Aiken appears recessive, unintimidating, a gentle giant who consistently drives women between the ages of 16 and 60 into a frothy lather of lust. In addition to the Rolling Stone cover, there are the requisite Web sites devoted to all things Clay, run by women who call themselves Claymates and shilling everything from Clay coffee mugs to Claytionary (stationary embossed with his face). And then there are the panties.

“I got seven one night,” says Aiken with a giggle. “And last night, I got five thongs and two Depend diapers. One had a note attached that said, ‘Clay, we love you too, from your older fans.’”

That women are so moved by his presence that they hurl their undergarments onstage as if he were Elvis mystifies Aiken: “Ruben always jokes with me that I could have any woman out there. He says, ‘You need to hook up with somebody before you leave the tour.’ But I try and explain that that’s not what this is about for me. The reason women like me, I think, is because I don’t threaten them. I realize Ruben’s right, I probably could”—he pauses, blushes—“you know, but I respect women more than that.”

He wrinkles his brow, then shakes his head. “I am extremely flattered. There are some gorgeous women who are, quote, in love with me. But I think taking advantage of that is wrong.”

Besides, Aiken is a man who takes sex seriously. “I was raised by my mother and grandmothers, and a lot of what I am is because I wanted to be different from my birth father. He was a womanizer. When I had to go visit him, there would be a different woman over every time. I thought that was really tacky.”

When it’s suggested that not many young men would forgo voluntary, anonymous sex with beautiful, knickerless girls, Aiken shrugs.

“If anything, women want to take care of me, to mother me. I think that’s part of the reason I’ve sold a lot of records.”

“If anything, women want to take care of me, to mother me. I think that’s part of the reason I’ve sold a lot of records.”

The other part is the fact that Aiken can wring the juice out of any song he sings. The vocal love child of Celine Dion and Freddy Mercury, he belongs to the grand tradition of powerful, house-rattling singers who own the money note. When you listen to Aiken, two things happen: You want to hear more, and you want to sing along. There’s also the unfiltered intensity of the sound mixed with the “Aw, shucks” innocent who’s creating it. That dissonance is what first captured the judges’ attention. “Where is that voice coming from?” they repeatedly queried, staring Aiken down, waiting for the true source to be revealed. Here was a sweet Southern mama’s boy who sang like a big bad man. No wonder the panties are flying!

INSIDE THE IDOL BUS

It’s four hours before show time, and crowds are already forming at the Hartford Civic Center. Many of the fans hold cardboard signs with Clay’s name written in big bubble letters. Other fans wear T-shirts printed with his photo.

Once safely beneath the stadium, Aiken emerges from the van and brushes the remnants of his Burger King fries off his pants. “I prefer Wendy’s, but they aren’t as popular up here.” He then explains how much he misses sweet tea, fried chicken, and all the other familiar amenities displaced Southerners long for when above the Mason-Dixon Line. “I had never left the state of North Carolina before American Idol,” he reveals. “I knew what I was going to be doing when I was 50—I was going to teach, then get a master’s at William & Mary in administration, then be a principal somewhere. Now I don’t know what I’m going to do next week.”

Even when Aiken talks, his voice is difficult to contain. The words rush out from his mouth in torrents, pitching and rising, quiet and loud.

“I want to live in Raleigh, but I know I can’t. I tried to go to the ATM the one day I was home last year, and people swarmed my car. I was like, People, please, I just want to check my balance. Ironically, the only place I can really breathe is L.A. People there don’t care.”

Just then, Studdard pulls up in a white Cadillac Escalade. He emerges in a white sweatsuit, his diamond watch blinging on his arm. He gives a friendly nod to Aiken, then scowls at his publicist for no ostensible reason.

“Don’t look at me that way,” she chides, patting his shoulder with a familiarity suggesting this isn’t the first time she’s had to diffuse his annoyance.

Aiken pulls me aside. He wants to show me the tour bus, something I was told was off-limits to reporters. Aiken disagrees and confronts a tour manager.

“Ned, you’re a lying sack of crap. Don’t lie to the lady in front of me.”

“I guess I forgot,” Ned says sheepishly.

“You didn’t forget for squat. Now we’re going to have to have a fight. That burns me up.”

Aiken turns to me and says through his teeth, “You know what? You are so going on that bus.”

Aiken is nothing if not chivalrous. Considerate. Polite. He’s the guy who asks you questions and actually listens to the answers—and even asks follow-up questions hours later, thereby proving that he finds you worth his attention. And he notices things. Like that the empty Burger King bag is rattling at your feet on the floor of the van, so he picks it up. Or that the air conditioner is too cold, and turns it down. It’s this empathy and inherent graciousness evident in every press appearance and performance that leads many men to speculate that Aiken is gay (he has denied it) and even more women to say, Who cares?

Aiken is nothing if not chivalrous. Considerate. Polite. He’s the guy who asks you questions and actually listens to the answers—and even asks follow-up questions hours later, thereby proving that he finds you worth his attention. And he notices things. Like that the empty Burger King bag is rattling at your feet on the floor of the van, so he picks it up. Or that the air conditioner is too cold, and turns it down. It’s this empathy and inherent graciousness evident in every press appearance and performance that leads many men to speculate that Aiken is gay (he has denied it) and even more women to say, Who cares?

“I don’t think people know what to do with me,” Aiken says. “I’m interesting because they don’t know what to do with me.”

The American Idol bus is less bus than nightclub. There are black leather lounge chairs, plasma TVs, marble floors, a neon-trimmed alcohol-free minibar, and beds with privacy curtains. As we open the back lounge door, Kimberley Locke (who came in third) lifts her head from the couch.

“Cla-ay,” she whines, “I’m having a crisis. I need you. I need you now.”

“Cla-ay,” she whines, “I’m having a crisis. I need you. I need you now.”

Aiken apologizes, then steps inside the lounge, says, “What is it, honey?” and shuts the door. Outside the bus, the other Idol girls walk around in skinny jeans and mascara, alternately complaining and striking poses like they’re on MTV. In time Aiken emerges, apologizes again, then sits down with the crew for a dinner of peanut butter and jelly and a glass of, yes, milk. He playfully scolds a staff member for swearing. Idol Kimberly Caldwell (the sixth Idol to get the hook) joins the table wearing a handwritten T-shirt that says QUIT STARING, I’M HER.

While she picks apart a cinnamon bun, Aiken tries to articulate his ambition.

“Am I going to turn into a diva or try to make sure I do something valuable with my influence?” Caldwell chews and looks off into the distance. “That’s why I’m starting a foundation for individuals with disabilities. [His charity, named the Bubel-Aiken Foundation, is named for the woman who encouraged him to try out for the show.] I would be more than happy to do this for three years and have enough clout to make a difference. I don’t need to win a Grammy. Still, there are some people who would say I’ve turned into a diva already.” Caldwell laughs.

Aiken proceeds to give an example of the last time he went to KFC. “It was half an hour before closing, and they said they were out of chicken. It’s KFC—how can you be out of chicken? So I’m starving and probably crankier than I should have been, and I said, ‘You don’t have any chicken in the building anywhere?’ And she said, ‘We have some wings that are kind of warm.’ I said, ‘I don’t want wings, I want chicken.’ And she maintains that she doesn’t have any, so I say, ‘You can’t tell me that every morning you go out and kill some chickens and make it fresh. You know you’ve got chicken back there, so why don’t you go back into the kitchen and cook it up?’”

Now the whole table is laughing.

Now the whole table is laughing.

“The point is, I would have said the same things before American Idol, but I wouldn’t have been considered a diva. I just would have been considered myself.”

“Where did you learn to sing, Clay?” Caldwell asks, flipping her shoulder-length extensions behind her neck.

“At church, like everybody else.”

“I learned at a bar,” scoffs Caldwell, pushing back her chair and heading to makeup. Aiken looks around, lowers his voice, then whispers, “I’ll bet she did.”

The Hartford show is sold out. Sixteen thousand people have come to watch the nine touring Idols sing and dance. The set resembles a beauty pageant, with dual staircases descending in a heart shape to center stage. There are three giant screens that simulcast the show. The tour is sponsored by Pop-Tarts.

Backstage, Aiken gets his hair ironed. He’s wearing a dark suit and pointy Kenneth Cole shoes. Next to him, all the Idol girls pile on the makeup and hairspray. Aiken rolls his eyes.

“You know, Ruben and I did the radio show Zootopia at Giant Stadium, and 60,000 people showed up. I just laughed, because I don’t get it. And people will chase the bus! And sometimes I laugh because, you know, we probably aren’t gonna stop, honey.”

“You know, Ruben and I did the radio show Zootopia at Giant Stadium, and 60,000 people showed up. I just laughed, because I don’t get it. And people will chase the bus! And sometimes I laugh because, you know, we probably aren’t gonna stop, honey.”

From the makeup mirror, Idol Julia DeMato announces that she and Aiken have been dating for six months. Uproarious laughter all around. Aiken says, “You wish.”

“I do wish,” she coos, kissing him on the cheek. Aiken smiles, wipes away the lipstick. “I think I’m probably not as innocent as I seem.”

Has he ever done anything he regrets?

“When I was 15, before I got my license, my dad bought me a car, and it was sitting in the yard, so I took it out. I drove it all around the city. I got caught and they sold the car.”

Rebel.

“Okay. How about I’m starting to regret this interview?”

The show has started, and it’s Aiken’s turn to sing. Kimberley Locke is onstage building him up, but you can’t hear her because of all the “Woo!”ing. A look at the audience reveals that it is not a bunch of preteens, but couples and groups of women in their twenties and thirties who are squealing and raising their arms in anticipation. “We love you, Clay!”

Lifted on a platform from beneath the stage, Aiken emerges like a mirage from a cloud of smoke, microphone in hand.

“When the world wasn’t upside-down/ I could take all the time I had/ But I’m not gonna wait when a moment can vanish so fast/ Lift me up!”

By the time Aiken hits the second chorus, the screaming makes him all but inaudible. He gamely keeps singing, but a smile slips through. It’s clear he can’t believe what’s happening.

Locke gasps. “This crowd is crazy.”

Aiken finishes his number, then does his bit to introduce “Ruben Studdard, your American Idol!” The crowd yells again, but the enthusiasm is different, more appreciation than hysteria. Studdard is a terrific singer, but Aiken is the star.

Aiken finishes his number, then does his bit to introduce “Ruben Studdard, your American Idol!” The crowd yells again, but the enthusiasm is different, more appreciation than hysteria. Studdard is a terrific singer, but Aiken is the star.

Backstage, calm and happy, Aiken holds Locke’s jacket while she mikes up. He adjusts her pants, tugging at them a little. “This is my real life now,” he says, dancing a little.

“I’m not going to change who I am. But I am concerned about how I handle myself. Will I be able to stay open and friendly?” His smile drops and he looks, for a moment, genuinely sad. Then he smiles again. “You come back in five years. If I’ve become someone else, you can look me up and slap me in the face.”

Back in the van, before the show and the fans and the shrieking, Aiken was stuck in traffic. He did not complain. He just told stories. About how he was approached about the leads in Rent and Urinetown. About how he can’t dance. About how Justin Guarini’s smoothness kind of gives him the willies.

And then he told a story about London, where he recorded his album.

“It was sunny the whole time I was there. But I was recording all day and everything closes at six, so I sat in the hotel room all night. I was only recognized once, when some South Africans who were still watching the show back home stopped me on the street. They said, ‘Who wins?’ I said, ‘Do you really want to know?’ And they said, ‘Yes! Yes! Yes!’ So I said, ‘Me!’ and then took off running down the street.”

Aiken laughs for a full minute, then exhales. “For one brief moment, I hadn’t lost yet.”